“A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” Mahatma Gandhi.

Whilst there is some argument over the exact translation of this quote, and in what context it was said, what is irrefutable is the truism at its core.

Being a victim of crime can be one of the most profound experiences of our lives. In the days, weeks, months and sometimes years following the incident, as we struggle to come to terms with the label of being a victim, wonder if we could of done anything different before realising that it is always the fault of the perpetrator and never the victim, and try to navigate our way through the criminal justice process, we may not necessarily know what help we need, just that we need it.

It is in exactly this situation, when we are particularly vulnerable and uncertain, that we need reassuringly confident and supportive victims’ services.

Since last October, the majority of emotional and practical support services for victims have been commissioned locally by Police and Crime Commissioners, replacing the previous model where services were delivered through a national contract managed by the Ministry of Justice.

Looking forward, come what may on election day, both Conservative and Labour have outlined manifesto commitments that place victims at the heart of criminal justice policy, and both main parties speak in broad terms about the introduction of a Victims’ Law that will place key rights for victims on the statute books and formally set out minimum entitlements and standards of service.

Of course, a new Victims’ Law will not be the first requirement for relevant criminal justice agencies, as the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime, the Witness Charter and the EU Victims Directive all have specific stipulations; although in practice these do not necessarily align as effectively as could have been hoped for.

We should not forget, however, whilst legislation and guidance are the stick, the carrot of the imperative to change which will always drive local improvement to a much greater extent. Indeed, victims themselves are often the key proponents for change experiencing as they do, for example, poor communication between police, courts and service providers that leads to the feeling of being passed from pillar to post.

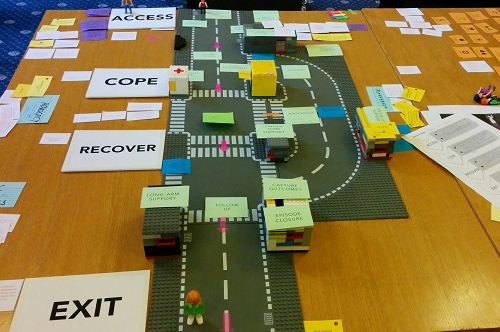

Local commissioners, providers and victims alike are all passionate about improving services, and over the past several months programmes of work have been underway to redesign local pathways to ensure a victim centred approach from start to finish, but with flexibility to account for local not national priorities, and delivery models that value the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector whilst preserving what already works well, and ultimately allowing the victim to cope and recover.

Commissioning and delivering efficient services is not an easy task. Every victim is an individual, and personal experiences of crime differ greatly. Two people, with broadly similar backgrounds who experience broadly similar crimes, might well have vastly different reactions and therefore require different levels of support. A victim of a violent assault might cope with their ordeal quickly and put it behind them, whilst a victim of credit card fraud might dwell on the repercussions of the event to such an extent that it pervades their everyday life.

In trying to design services that can account for this variability, a one size fits all approach is not going to work. Add to this the fact that despite a year-long exercise to try and stimulate the marketplace, when it came to recommissioning services from April, the vast majority of PCCs have gone with the same major supplier. It is in no way a reflection on this supplier, but it in the interest of improving victims’ services to encourage the diversification of supply. However, the sector is still undeveloped and many voluntary and community providers in particular are unable to compete with larger providers who have significant experience of the tender process and can rely on an infrastructure of bid writers as well as legal and commercial support.

There are also new skills that commissioners, in particular PCCs need to acquire. To date, PCCs have chiefly administered their budgets through a grant funding process, but in the move to fully fledged commissioning and contract management a new series of skills are required. Crucially, PCCs must be able to demonstrate that their decisions are wise – commissioning on the basis of a local evidence base, aligning the effort of partners around a key set of agreed priorities and demonstrating best use of the public purse.

Our police governance bodies are still finding their way in this new world of locally commissioned and accountable services. Time will tell, but PCC-led commissioning should bring about the desired improvement in the quality of victims’ services, given local oversight and local ownership of local delivery within the local community. At this stage, what is clear is that this may well be the biggest challenge yet for PCCs.

This article was previously published on Policing Insight.

Leave A Comment