Pot meet kettle. The Commons Select Committee report on police diversity (Police Diversity, May 2016) is unsurprisingly incendiary. Headline key facts include that:

- in 2015 only 5.5% of police officers were from a BAME background compared to 11.4% of the working population; and

- no Force in England and Wales has a BAME representation which matches the local demographic, indeed four Forces (Cheshire, North Yorkshire, Dyfed-Powys and Durham) all employ no Black or Black British officers.

Again unsurprisingly, many commentators point to the lack of BAME representation in Parliament, noting that those in glass houses might want to think twice before throwing stones. Their point is well made.

Irrespective, focusing on this aspect does the wider issue a disservice.

So let’s get a few myths out of the way, and try to get to the heart of the matter.

The best person should be recruited, regardless of any protected characteristic

Of course. The College of Policing guidance (Positive Action: Practical Advice, October 2014) citing the Equality Act 2010, states that:

“Positive action does not mean people will be employed or promoted simply because they share a protected characteristic. Rather it aims to encourage and assist people from disproportionately under-represented groups in order to help them overcome disadvantages associated with the protected characteristic when competing with other applicants, or to enable them to participate in the activity.”

Practically this means that if the recruitment process highlights a number of candidates as being “as qualified as or of equal merit” it is lawful to give preference to a candidate from an under-represented group where the employer in question has already identified it has low levels of representation.

Reports like this are just another example of police bashing

Well, perhaps. The statistics presented in the report are fair, and there is nothing to suggest they are in any way inaccurate. However, the fact that only 5.5% of officers are from a BME background is simply not good enough and more must be done to improve this. The report rightly cites a number of examples of good practice from right across the policing family.

However, by placing the focus on policing, the report omits wider structural and societal considerations that also play a part. Whilst the report does acknowledge that the responsibility for improving this situation does not solely lie with the police, by stating that “we believe that it is time for concerted action, prioritised across all forces, policing bodies and Government,” it does not take the time to consider what these wider factors are or how they could be improved.

But equally, perhaps not. Policing is unique. Unlike other professions, including binmen, one of the core principles of policing is that warranted officers are the public which they serve. Policing by consent recognises that police officers must reflect their communities, and those forces who do not lose credibility with those communities. No other profession had this foresight or this foolishness. Therefore, it is understandable why policing is held to a higher standard, and perhaps others could be somewhat forgiven for expecting more from policing than they do from their own professions.

As an aside, and perhaps in an attempt to even out the criticism of the police, consider the recent PCC elections. Just three of the PCC candidates were BME, or 2% of the entire candidate pool. Given that 84% of candidates were standing on an official party ticket, we can conclude that political parties did very little to encourage the ethnic diversity of their candidates. This was certainly an opportunity lost.

BME communities do not see policing as a viable career

This is somewhat true, and the reasons are complex and enduring. From those who experienced brutal policing regimes in other countries, through those whose experience of growing up in our inner cities during the sixties and seventies forever tainted their view of policing, to those whose experience is more current the stories told and views shared can be equally negative. We are decades past the Scarman Report into the 1981 Brixton riots and the Macpherson Report into the 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence, but any time things go wrong communities tell us that nothing has changed.

More recent and well publicised experiences of BME officers from across all forces who ended up losing careers they loved exacerbate this view. The fact that there are incredibly few BAME role models (two Chief Officers self-identify as BAME) tells twentysomethings who might be thinking about entering the service that the glass ceiling is still there, irrespective of whether that is true or not.

The sad truth is that we continually fail to attract a representative mix of applicants. We press ahead with trying to reach out to under-represented communities without first really understanding why they do not regard policing as a viable career. However, the US, which could be regarded as more polarised and less inclusive does not have the same issue. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (2013) found that 27.3% of America’s police officers are BAME, with 12.2% being black compared to the overall population of 13.2%. Why have they succeeded where we have failed – is it simply just about entry level pay, or are there wider considerations?

Equal representation is a myth

OK so this one is mine.

From a purely statistical perspective, if we continue to compare the proportions of BAME officers with those of the wider population we will continue to be disappointed forever.

The facts are that BAME individuals are not represented at all levels in the police service, or elected office, or within the vast majority of Britain’s other workplaces. All too often policing takes the brunt of this, where in actuality it applies in all professions, at all levels, throughout all of society.

Last year the College “estimated that the BAME population of England and Wales will be 16% of the total population by 2026” and that “the police service would need to recruit approximately 17,000 BAME officer over the next decade to achieve a more representative profile.”

Whilst this is not a target, it is clear that if it was, it most likely would not be achieved. And in 2026 the goalposts would move again as the estimated BAME population for 2036 would be even higher. As populations and cultures mix and assimilate into our fantastic melting pot, the concept of a “minority ethnic” population will become something of a misnomer.

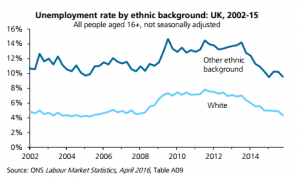

Additionally, the elephant on the room is the structural considerations around employment parity. The House of Commons Library research (Briefing Paper 6385, April 2016) clearly shows that disparity in the UK unemployment rate (the proportion of the economically active population who are unemployed) between those from a white and those from other ethnic backgrounds.

The Home Affairs Committee has called for “urgent and radical action” to address the issue of BME under-representation in policing, and recommended the appointment of a national Diversity Champion by the Home Secretary. Great idea. I respectfully suggest that this person’s first task should be to highlight the fact that this is not solely a policing issue, and that by tackling the societal causes of inequality and the barriers to employment faced by BAME communities many, if not most, of the specific problems present in policing will fall away.

Leave A Comment